Editor: Jaap Horst

While kitchens and cockpits are both high pressure, high temperature environments, it’s a rare man that moves from one to the other.

While kitchens and cockpits are both high pressure, high temperature environments, it’s a rare man that moves from one to the other.

Noted pre-war racer Rene Dreyfus spent the 1930s competing in grands prix across Europe, but became a New York restaurant owner in the 1940s. An odd choice of career change, you might think, but one that makes sense in a historical context.

Rene Dreyfus was born in May 1905 in Nice, the middle child of a Jewish family. While his religion shouldn’t have been of any significance to his career, Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the subsequent Second World War meant that for many in Europe, being Jewish was the difference between life and death.

But until Dreyfus reached his mid-thirties, his religion was of little consequence to his professional life. The French driver first got behind the wheel at the tender age of nine, having been interested in cars as soon as he was old enough to express an interest in anything.

Despite his early automotive start, it would be another ten years before Dreyfus began to race. While he won his class in the first race he entered, it was not a mind-blowing victory. Dreyfus was the only entrant in his class at that 1924 amateur event.

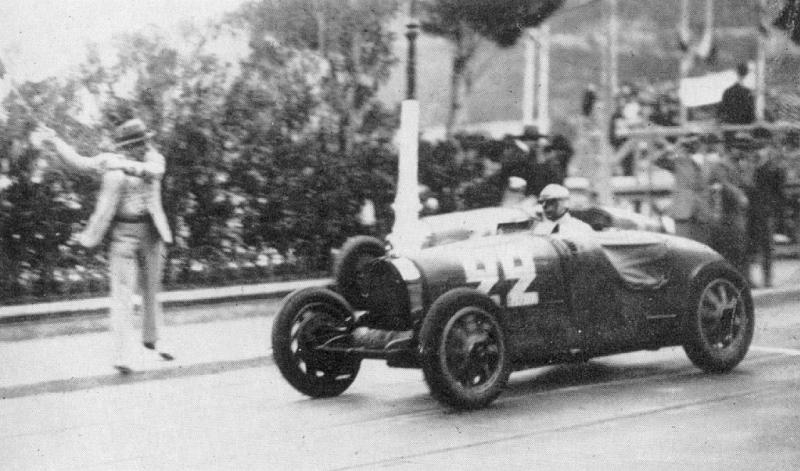

But the victory was a sign of greater things to come, and between 1924 and 1929 Dreyfus entered a host of amateur events around the French Riviera, winning five championships and honing his racecraft. His driving attracted the attention of a local Bugatti agent, who offered the young racer a chance behind the wheel of one of the company’s cars at a few 1929 events, including the legendary Targa Florio, the maiden Monaco Grand Prix (where Dreyfus finished first in class and fifth overall), and the Dieppe and Marne Grands Prix.

At the 1930 Monaco Grand Prix, Dreyfus impressed all and sundry when he won the race outright, beating the Bugatti works team in the process. Aware that works cars were nearly impossible to beat, Dreyfus added an extra fuel tank to his Bugatti, reasoning that the added weight would be cancelled out by the time saved not stopping to refuel. It was a brilliantly tactical manoeuvre that earned him respect among racing professionals, and sealed Dreyfus’ reputation as an up and coming young racer to watch. You can see footage from the race in the clip below.

It was in the 1930s that Dreyfus’ career really took off. He followed up his Monaco victory with overall and class wins at the 1930 Marne Grand Prix, the 1930 Grand Prix d’Esterel Plage, the 1931 Grand Prix de Brignoles, the 1934 Belgian Grand Prix, the 1935 Marne Grand Prix, the 1935 Dieppe Grand Prix, the 1937 Tripoli Grand Prix, the 1938 Cork Grand Prix, and the 1938 Pau Grand Prix, footage of which can be seen in the grainy clip below.

It was in the 1930s that Dreyfus’ career really took off. He followed up his Monaco victory with overall and class wins at the 1930 Marne Grand Prix, the 1930 Grand Prix d’Esterel Plage, the 1931 Grand Prix de Brignoles, the 1934 Belgian Grand Prix, the 1935 Marne Grand Prix, the 1935 Dieppe Grand Prix, the 1937 Tripoli Grand Prix, the 1938 Cork Grand Prix, and the 1938 Pau Grand Prix, footage of which can be seen in the grainy clip below.

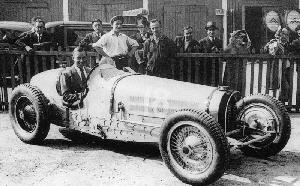

But this list of victories fails to paint the full picture of Dreyfus’ career. In 1931, the young Frenchman joined the Maserati team as a works driver. But the cars were uncompetitive, and he moved to a role with the Bugatti team at the end of the following year. In 1935, Dreyfus swapped teams again, this time to Scuderia Ferrari. He stayed there until 1937, when he made the move to Delahaye.

The 1930s were a time of change in motorsport, as by the middle of the decade the influx of government money into German motorsport efforts meant that the cars to beat were those run by the Mercedes and Auto-Union teams. Top drivers of all nationalities were enticed to drive for the German teams, tempted by the competitive machines, high salaries, and innovative cars being produced. As a Jewish driver, Dreyfus was not welcome in a German car.

As the decade progressed, Europe became a more dangerous place in which to be Jewish. Dreyfus was a French citizen, so safe from Hitler’s reach, but when war broke out in September 1939, no one was safe any more.

Dreyfus enlisted in the French army, and was put to work as a truck driver. But in 1940, the French government sent their famed racing driver to the United States, where he was to drive for Maserati in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Memorial Day 500. Dreyfus and his co-driver suffered problems in qualifying, and in understanding the rules, but managed to finish in tenth place despite the confusion.

By the time Dreyfus was scheduled to return to France, the Germans had taken Paris. As a high-profile Jew, he was advised by his government to remain in the States. Dreyfus heeded the advice, and settled in New York City. But in 1942, shortly after the Americans entered the Second World War, he enlisted with the US Army and fought to free Europe from the clutches of Nazism, serving as an interrogator in the Italian Campaign.

After the Second World War ended, Dreyfus returned to New York and became an American citizen. In 1945, he and his brother Maurice, who had served as his manager in Dreyfus’ racing days, opened a French restaurant called Le Gourmet, which soon became a place for the world’s racing community to see and be seen. In 1952, nostalgic for his homeland, Dreyfus sold the restaurant and returned to France.

After the Second World War ended, Dreyfus returned to New York and became an American citizen. In 1945, he and his brother Maurice, who had served as his manager in Dreyfus’ racing days, opened a French restaurant called Le Gourmet, which soon became a place for the world’s racing community to see and be seen. In 1952, nostalgic for his homeland, Dreyfus sold the restaurant and returned to France.

But in much the same way as he could not get racing out of his system, Dreyfus had been bitten by the restaurant bug. In 1953 the brothers returned to New York and opened a second restaurant, Le Chanteclair.

Even in his days as a restaurant owner, Dreyfus could not get motorsport out of his system. In 1952, he took part in the Le Mans 24 Hour endurance race. In 1953, he added to his endurance racing experience with an attempt at the Sebring 12 Hour race. And at the grand old age of 75, Dreyfus did a driving tour of Europe, taking in all of the scenes of his racing successes.

Rene Dreyfus died in New York City in August 1993.

This article was first published on www.girlracer.co.uk