Editor: Jaap Horst

Even by modern standards, the definitive Bugatti T35 is a sensational performer. Mike Walsh looks under its beautiful skin to discover creator Ettoreīs secrets

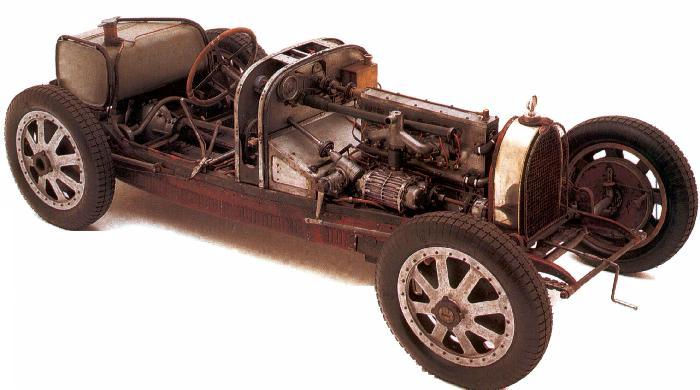

If there's one car that fits the description 'rolling sculpture' it's Ettore Bugatti's supremely elegant Type 35. From its horseshoe radiator to pert tapered tail, it has an exquisite fitness of form from every angle. But strip away its five body sections -a task that takes just

10 minutes- and the Type 35's mechanicals are even more enthralling. Clever, idiosyncratic, efficient, artistic, ingenious and occasionally blinkered, Ettore's design work reached its peak with this production racer. "It was the first Bugatti that: was a complete design," says marque specialist Tim Dutton, "a crystallisation of all his earlier ideas and, for its day, the package was very advanced.

"The car shows a real appreciation of stresses and loads and, although no one element was exceptional, the fine handling, strong brakes and good performance made it difficult to beat. As a racing car designer, his work never got any better. Unlike the Miller-influenced twin-cam Type 51, this car was pure Bugatti. He undoubtedly had a good team of draughtsmen, but Bugatti conceptualised the design ideas

in a Chapman-esque way. He was a very clever man."

The handsome, tapered frame that curves out to the period GP-width cockpit is brilliandy stressed and uses the cast engine sump to brace the frame's centre. Unlike rivals, no boxing-in was required and, from its 1924 debut at Lyon to the final 1932 Type 51, it remained virtually unchanged.

The handsome, tapered frame that curves out to the period GP-width cockpit is brilliandy stressed and uses the cast engine sump to brace the frame's centre. Unlike rivals, no boxing-in was required and, from its 1924 debut at Lyon to the final 1932 Type 51, it remained virtually unchanged.

The tall, narrow, square-cut engine, with mottled finish, is unmistakably Molsheim. The monobloc design (two blocks of four stuck together) has no gaskets to fail and compact internals featuring parallel, vertical valves operated by a single camshaft with rocker arms - as recently revived by Ferrari's F1 team. Although compression could be stronger, gas speed is improved with siamesed inlet valves and a single exhaust. Due to poor breathing the combustion chamber was relatively inefficient so supercharging was a natural development to raise power. "The flat piston top is fine," says Dutton, "but the biggest downside was mounting the plugs on the inlet side. Modern engineers sneer at this but there were probably practical reasons for the choice. First there's the consideration of mechanics avoiding getting burnt fingers but also the original plugs didn't like the exhaust heat. Even fuel was closely routed to cool them."

Reliability is the strongest point of the roller bearing crankshaft which, fully dressed, weighs 170lb: "Most proper race cars of the 1920s had roller bearings. Oil surge isn't a problem and they will run on just a mist of oil while white metal engines such as Alfa and Maserati were forever putting rods through the side." The crank's oiling system runs through a centrifugal groove, which also acts as a filter, and has to be rebuilt every 10-12,000 miles to avoid a seizure: "If the owner is less mechanically aware - a good driver can feel when the engine is tightening - a strip-down is advisable after 6-8000 miles. Also, warming up at constant rpm is essential to avoid the rollers skidding and flatting. Now, when the tracks are worn, we convert to needle rollers."

Even today in historic paddocks you'll see mechanics frantically trying to replace a supercharger after the engine has coughed back and broken the vulnerable direct drive. Bugatti chose a simple three-lobed Roots-type unit but solved this problem with an ingenious drive using leather couplings to absorb the mechanical sneeze. The Zenith carb was good for its original race use, but for trips down to the pub the idle progression system is poor. As Dutton puts it: "The barrel throttle is not geared for slow running in traf- fic, but when fully open the big hole works fine."

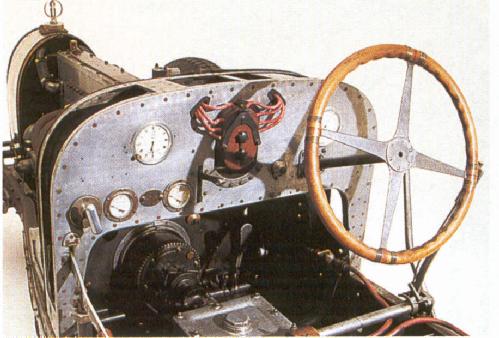

The magneto, distinctively mounted in the centre of the dash, has a unique drive with a linkage on a scroll fitted on

the drive from the engine in front. This allows you to

mechanically alter the advance and retard without adjusting the points, thus giving a big spark at all positions. "It's a good diagnostic tool if nothing else," says Dutton. "When you're blasting down a straight and want to try a little more retard or advance, the position of the magneto to the engine changes but not the point of maximum flux."

The pressurised fuel tank sits right over the back axle (good weight distribution again) and is primed with a simple hand pump on the dash. Big pipes were essential to feed the thirsty engine

which, on pump fuel, does lO-l2mpg but on methanol guzzles up to a gallon every two miles at full chat, For a race, Dutton reckons on a gallon a minute to be safe.

The distinctive eight-spoke wheels are another classic Bugatti design, By casting the brake drum integrally with the wheel you change the drum and gain instant access to

the shoes as soon as the wheel comes off. The aluminium is a good heat sink and the wide surface area helps with thermal transfer, Cable operation may look like it's borrowed from a bicycle but the details are fiendishly clever. Each side has a cable that works both front and rear brakes with a chain section in the middle. This runs over two cogs, the second linked to the brake pedal shaft and, when you press the pedal, the cogs run along the chains until the tension is even before the cable starts to pull. The pedal also has bevelled gears, allowing it to swing from side to side. "It's ingenious and feels like an hydraulic system," explains Dutton. "You'll never see a Bugatti driver leaping out to adjust the brakes unlike the rod design on Alfas. The only problem is that heavy braking effort at the front can lock up the wheels and twist the axle."

The distinctive eight-spoke wheels are another classic Bugatti design, By casting the brake drum integrally with the wheel you change the drum and gain instant access to

the shoes as soon as the wheel comes off. The aluminium is a good heat sink and the wide surface area helps with thermal transfer, Cable operation may look like it's borrowed from a bicycle but the details are fiendishly clever. Each side has a cable that works both front and rear brakes with a chain section in the middle. This runs over two cogs, the second linked to the brake pedal shaft and, when you press the pedal, the cogs run along the chains until the tension is even before the cable starts to pull. The pedal also has bevelled gears, allowing it to swing from side to side. "It's ingenious and feels like an hydraulic system," explains Dutton. "You'll never see a Bugatti driver leaping out to adjust the brakes unlike the rod design on Alfas. The only problem is that heavy braking effort at the front can lock up the wheels and twist the axle."

The beautiful front axle is similarly inspired for its era, with hollow centre and solid ends. This is achieved by forging the axle straight, boring a central hole right across, slotting out two square holes for the spring to pass through and then forging down the ends to solid again. Finally it was bent to shape for machining and polishing. Strong and light, it also scored with unsprung weight.

Instead of bolts, the location is secured with wedges which makes it ideal to play around with caster angles: "It's easy to adjust it to suit a fast circuit like Monza, where you want lots of caster, or Monaco, where the direction is forever changing. The steering is marvellous - direct and precise. Also available were different lengths of steering arm which could alter the action depending on the track. A short drop arm provides a lighter feel for road circuits, but for Montlhery you'd want something heavier. Such tuning wasn't done in the 1930s, but you can with this car."

The steering box is a simple casting of great rigidity with the worm and wheel properly encased. On some Targa Florio cars thrust ball races were used on the worm to reduce steering forces. The box and column are well mounted but, on supercharged models, had to be moved back and carried on a shoe extension to make room for the blower. The wood-rimmed four-spoke wheel looked great, but in accidents the original, fine-grain walnut-rim sections had a habit of splitting and impaling the driver.

Bugatti's own shock absorbers were also not so clever and are difficult to adjust: "When set up properly they work much better than Hartfords. Working in a case of grease they don't suffer from stiction and, from a control view- point, they have an almost hydraulic feel. The key to the car is correct set -up. Over the past 30 years enthusiastic owners haven't really appreciated the finer points of tuning which is why cars have wildly different driving characteristics."

Springing at the back is by reversed quarter elliptics splayed out to follow the tapered chassis, giving excellent side location and improving unsprung weight. This unusual feature was later copied by Alfa Romeo for the Tipo B. The rapid action of the Type 35's straight-cut gearbox, operated by a right-hand lever outside the bodywork, is a special driving feature. The compact design, with light constant- mesh gears, dates back to the Brescia, but Ettore had the novel idea of connecting the layshaft to the output shaft rather than the input shaft as with most conventional gear- box designs. This reversed layout allows the gears to slow down quicker, resulting in the model's electric change.

"It's like a motorbike," Dutton adds. "Absolutely fabulous. The key is to move it as fast as you can. The gentler you try to be, the worse it gets." The clutch is another clever, compact feature, with nine small-diameter alternate iron and steel discs (only 5.5in like a modern competition car) running in oil: "The clamping force is done with an over-centre toggle mechanism so the pedal pressure is relatively light for a clutch that has to take 180lb ft of torque."

The back axle, another handsome casting, features a strong off-centre torque arm giving 100 per cent anti-squat off the line so the car rises: "The idea is similar to American dirt-trackers. As the torque reaction is taken out through the arm it allows for relatively soft springs, giving a good ride and tremendous traction." Acceleration is startling too, with 0-60mph in under 6 secs.

TARGA CHASSIS 4871

TARGA CHASSIS 4871The amazingly original Type 35C featured is one of a pair of factory team cars entered for the '28 Targa Florio, driven by Chiron and Foresti, its first private owner, Mme Jannine Jennky, registered it for road use. The opening picture is of Jannine Jenny, after winning the 4 Hours of Burgundy in 1928. Its competition life continued with Ricardo Bernasconi,who retained it until 1958. He registered it on March 2 1932 with: 2515 KJ 2, the registration it still shows. On Ettore's advice the car was repainted in Italian racing colours and, when he retired from racing,the red Bug' was stored in an old Marseilles shop with whitewashed windows to conceal it from prying eyes. The famous 'Bugatti hunter' Raffaelli spotted it one night when the headlamps of his car picked out its silhouette but he couldn't afford the FFrl 500 asking price. From 1958 it went to Belgium where it remained unrestored until revived for its new owner by Ivan Dutton.

Info on the cars early life from Antoine RaffaŽllis book Memoirs of a Bugatti hunter.

The article was reprinted with permission from Tim Dutton and Classic & Sportscar. The above article was taken from Classic and Sports March 2002, to Purchase this and other back issues please call Haymarket Reprints on +44 1235 534323, E-mail: letters.classicandsportscar@haynet.com. (no website available)