|

By Tony Hubner - Published first in "VIME"

After my recent trespass into the fields of internal combustion and rubber tires, I think some sort of redress is required. My subject remains Bugatti, but the theme is steam.

In my last piece I made reference to a series of high-speed railcars manufactured by Bugatti to soak up a surplus of 14 litre straight eights left on his hands by the depression of the ‘thirties. Following the success of the railcars, Bugatti was approached by two French railroads to produce longer-ranged complete passenger trains. The brief demanded that the trains be steam powered and oil fired. Bugatti with his chief design engineer, Noel Domboy had ten days to put together a proposal.

Their working arrangement, as recorded by Monseur Domboy is interesting. Following discussions Domboy would repair to the drawing office and with some draftsmen would prepare formal drawings. After hours, le Patron, as Bugatti liked to be called, would enter and study the work , leaving notes and amendments sometimes far into the night. Oh to have been a fly on the wall at start of work next day!

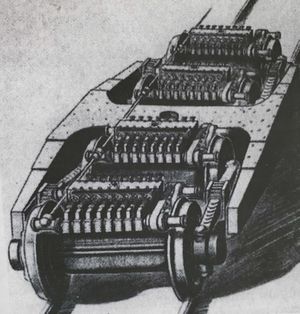

Sketch of the bogie with engines

|

The design they produced is fascinating: a streamlined locomotive on two eight(!) wheeled bogies followed by a tender/baggage car of matching cross-section towing a series of light passenger coaches with the same cross-section, all on similar eight-wheeled bogies. The original gasoline (The railcars actually burned a mixture of gasoline and alcohol, France had a huge surplus of industrial alcohol at the time. The railcars became less economic as this was consumed.) railcars had 8-wheeled bogies, a Bugatti original with longitudinal leaf springs. It was said that a two foot section of rail could be removed without affecting the cars progress. Another of his innovations was a layer of rubber between the wheel center and tire, vulcanized in place. The railcars were known for their smooth ride.

There were to be two versions of the locomotive: one of 1000 horsepower, one of twice that. To me the most fascinating aspect of the whole design was in the application of power to the wheels; each driven axle consisted of a single acting in-line eight cylinder engine slung between the wheels, each engine developing 250 horsepower. The stronger loco had both bogies powered, on the lower-powered one, the trailing bogie was an idler.

Steam was to be supplied by a water-tube boiler behind the driver’s cab supplying steam at 710 lbs. psi. Exhaust was to be condensed completely, so the entire roof of the locomotive was covered in condensers topped by an array of fans. One reason for oil firing, had to do with maintenance, mostly the elimination of the problem of ash removal, always a headache with coal-firing. What sets the range a conventional steam loco can travel is the volume of the ash-pan, whose size is limited by wheels, axles and mainframes.

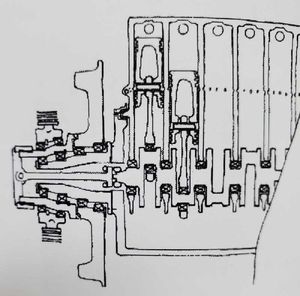

Part drawing of the engine and wheel

|

The crankcase of the engine acted as a dead axle on which the wheels revolved, drive taken to the wheels by a small shaft through the hollow wheel center around which another series of roller bearings connected to the leaf spring suspension. The engines turned roughly 1000 rpm at 90 miles an hour.

A chronic problem with a single-acting steam engine with a closed crankcase is condensate oozing past the pistons and getting into the sump. Bugatti’s solution to this was to have a conventional trunk piston, but very long, with the usual four rings at the top, then a section of reduced diameter slightly over the stroke in length, then back to full diameter with another set of rings. This left an annular chamber in the cylinder where the condensate collected to be drained away through small holes in the cylinder walls. Pity it was never tested in operation.

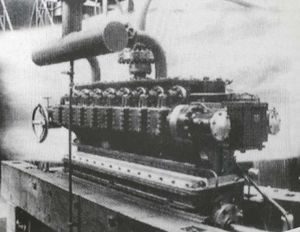

One such engine was built and dynamometer tested (and still exists!), but only at 250 lbs. psi from the factory’s own boiler. Apparently it exceeded its theoretical performance, both in power and economy. Admission and exhaust were controlled by poppet valves on either side of the cylinder; a “tee head” configuration. These in turn were actuated by “three dimensional” cams whose shafts could be shifted longitudinally to adjust cut-off and provide reverse. Between the cams and valve stems were rockers with hardened balls riding on the cams.

Photo of the engine on the test bench

|

As with most Bugatti eight cylinder engines, these were “Two fours”, that is cranks for four cylinders at one end were all at 180 degrees to one another, the remaining four were similarly disposed, but at right angles to the first lot. One consideration of the rail authorities was minimum effect on track work, which was certainly not an issue with these trains.

As a concept, these trains anticipate the Trains Grande Vitesse (TGV’s) of more recent times, in fact that entire species of high speed trains in service around the world, light, fast intercity unit trains. Ettore Bugatti, as a leading exponent of high performance internal combustion vehicles certainly brought the unique stamp of his own genius when it came to steam power! I personally think these trains would have been a great success; most of his stuff not only worked well, but became world-beating!

My own quibble with the concept lies in the fact that each axle seems to have been independently powered, making real the risk of individual axles breaking traction and slipping, but this could easily be rectified by, say, an over-speed trip, but given the superb suspension proven on the railcars, it may never have been an issue. We’ll never know!

We can only imagine what sort of spectacle these sleek trains would have presented, gliding along, all thirty-two or sixty-four pistons doing the revs at speed or gliding onto a station platform – no choo-choo, no clouds of steam, slight haze at the boiler stacks. I suspect the loudest noise would have been the oil burners – a sound to be heard by no one.

I hope they’d have had decent whistles, not air horns!

Top image: Sectional drawing of the locomotive, to be to the full height of the loading gauge to accommodate the boiler. Reduced at the right height of the train.

Below: some more drawings

|