Editor: Jaap Horst

For years it was accepted that only three Atlantics had ever been built, but recent books by Pierre-Yves Laugier and L. G. Matthews, Jr., have revealed the existence of another, chassis 57453, the first black one. Careful examination of period photos appears to support their opinion. Reading further, one learns that the whereabouts of 57453 is unknown and that it may have been destroyed or dismantled and lost. So much for what might have been very good news.

There is a next best thing, however, and it is a truly remarkable achievement: Erik Koux has built thirteen replica Atlantics. They appear as if they had just left Molsheim and the year is 1938. They are not mere look-alikes; they all have original Bugatti parts and precisely remanufactured duplicates. T57 engines converted to dry sump and double oil pumps power all but two of them. Donor Bugattis provide parts and titles.

And yet there is no intent to deceive, The original Atlantics and the Koux recreations are so few and so well known that there can be no suggestion of passing one off as the other. No less a devoted Bugattist than Andy Rheault told me how impressed he was with them.

The story behind these second-generation masterpieces began when Erik, then a young engineering student in Zurich, made the big switch from two wheels to four. The four wheels belonged to a 1933 MG-L2,

which he had to reassemble with the help of friends. Eager to move up after a while to "something more interesting", he soon managed to buy chassis 37155, a 1926 GP car that he had noticed in front of a Zurich bar. The negotiations resulted in his paying slightly more than he might have but still less than $200. This T37 was his introduction to Bugattis: he had never seen one before. He used it regularly, traveling back and forth between Zurich and Copenhagen at least a couple of times a year for holidays. In the mid-sixties he moved up again to a T57 Ventoux, which became his regular driver until he got an irresistible offer from Bart Loyens in Luxembourg. By this time Erik had accumulated a number of original Bugatti parts for future use including a front axle, a few wheels, etc.

The story behind these second-generation masterpieces began when Erik, then a young engineering student in Zurich, made the big switch from two wheels to four. The four wheels belonged to a 1933 MG-L2,

which he had to reassemble with the help of friends. Eager to move up after a while to "something more interesting", he soon managed to buy chassis 37155, a 1926 GP car that he had noticed in front of a Zurich bar. The negotiations resulted in his paying slightly more than he might have but still less than $200. This T37 was his introduction to Bugattis: he had never seen one before. He used it regularly, traveling back and forth between Zurich and Copenhagen at least a couple of times a year for holidays. In the mid-sixties he moved up again to a T57 Ventoux, which became his regular driver until he got an irresistible offer from Bart Loyens in Luxembourg. By this time Erik had accumulated a number of original Bugatti parts for future use including a front axle, a few wheels, etc.

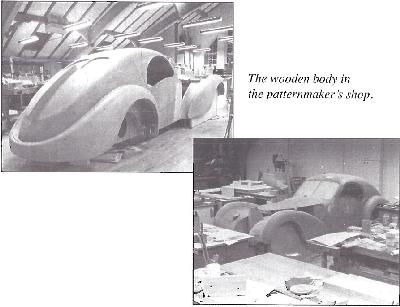

Bugatti parts were still readily available in Europe if you knew the right people, and by that time Erik had met many of them. He wanted to build a car with a simple body around T57 parts for himself . Bo Andersen, a friend of Erik's who was a patternmaker and had already made patterns for cylinder blocks and T51 wheels and had the facilities for producing fiberglass bodies, offered to work with Erik if they could build two cars, one for each of them. At that point "plans were changed," Erik says. "We decided to concentrate on the most complex project we could imagine."

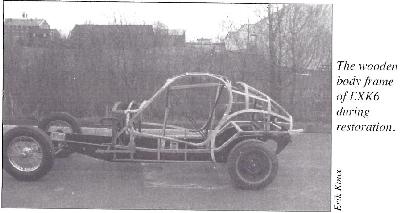

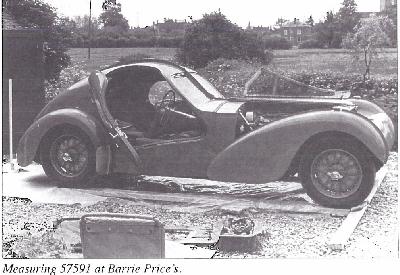

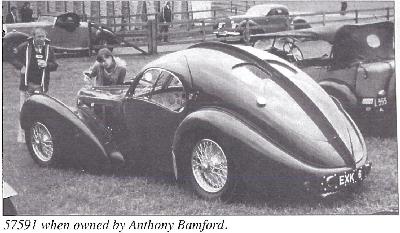

The Atlantic that now belongs to Ralph Lauren. registration EXK6, chassis 57591 , was then the property of Englishman Barrie Price whom Erik also knew. Price agreed that Erik and Bo could come to study and measure his car. So in 1974 they spent a week in England measuring,

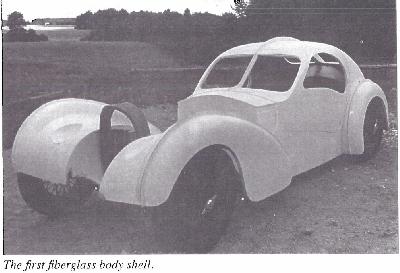

making templates and taking "at least a hundred photographs." The next step was to make a 1:1 scale body in wood. Since both of them had families and jobs, they could devote only one evening a week to the project, working from 5 PM until 2 the next morning. It wasn't until 1980 that they had progressed far enough to cast the first body in fiberglass. They had Bugatti parts for everything but the engines and decided that a Jaguar or a 2600cc Alfa engine would do temporarily. The two cars were still just for the two of them with no plans for commercialization.

The Atlantic that now belongs to Ralph Lauren. registration EXK6, chassis 57591 , was then the property of Englishman Barrie Price whom Erik also knew. Price agreed that Erik and Bo could come to study and measure his car. So in 1974 they spent a week in England measuring,

making templates and taking "at least a hundred photographs." The next step was to make a 1:1 scale body in wood. Since both of them had families and jobs, they could devote only one evening a week to the project, working from 5 PM until 2 the next morning. It wasn't until 1980 that they had progressed far enough to cast the first body in fiberglass. They had Bugatti parts for everything but the engines and decided that a Jaguar or a 2600cc Alfa engine would do temporarily. The two cars were still just for the two of them with no plans for commercialization.

On a to France in 1981 to celebrate the Centennial of Ettore Bugatti's birth, Erik met the son of John North II. North's father owned a Bugatti T57S and two Ray Jones replica T57S chassis. When North showed interest in two Atlantic bodies, Erik and Bo quoted a price, which was accepted, and things progressed more quickly as they worked on the two bodies for North along with their own. In less than a year they had produced two bodies complete with windows, doors, door hinges, instrument panels, etc., and sent them to North in the US.

The first of their own cars was finished at about the same time and had all original or reproduced Bugatti parts except for the Alfa 2600 engine and gearbox. It was seen at Vincennes, near Paris, and elsewhere in France and attracted the attention of several collectors who liked the car but wanted Bugatti engines and aluminum bodies. As thoroughly as they had studied EKX6 at Price's, they had not, of course, been able to take it apart to study its innards. At this point. fortune smiled on them.

Ralph Lauren had bought EXK6 from Thomas Perkins and sent it to Paul Russell's in Massachusetts for a complete restoration) (see Pur Sang

vol. 30, no. 4, Fall 1990), which would require the disassembling needed for a detailed examination of every bit of the car. inside and out. Another friend of Erik's, Jack Braam-Ruben, owned a T57 Galibier and wanted to donate it as a parts car for a Koux Atlantic. He arranged for Erik to go to America to visit Paul Russell's shop.

Ralph Lauren had bought EXK6 from Thomas Perkins and sent it to Paul Russell's in Massachusetts for a complete restoration) (see Pur Sang

vol. 30, no. 4, Fall 1990), which would require the disassembling needed for a detailed examination of every bit of the car. inside and out. Another friend of Erik's, Jack Braam-Ruben, owned a T57 Galibier and wanted to donate it as a parts car for a Koux Atlantic. He arranged for Erik to go to America to visit Paul Russell's shop.

A mutually advantageous deal was struck with Russell, who hadn't worked on a Bugatti before. Erik would supply technical advice and provide all the information he had about the car in its original condition. (There had been another owner between Price and Perkins, Anthony Bamford, who had done an incorrect restoration of the interior.) In return, Russell would allow Erik to draw and photograph as much as he wanted. The account of the restoration in Pur Sang gives ample evidence of how helpful this opportunity was: no stone-or rivet or bit of horsehair padding-was left unturned by Russell's team. All the information was there to be seen. Erik continues the story

I was now ready to start work on Jack's car. I had met a man in France who had employed a retired panel beater, and he offered to make the body as he wanted to build an Atlantic himself. He got my fiberglass molds to define the shapes, and I took care of all the hardware like windows, door locks and hinges, etc. We had also found a supplier for the T57S chassis frame who did a very professional job. We even managed to find 3.5 mm thick steel plate, which is the correct thickness for the frame but today you only find 3 mm or 4 mm sheet metal. In 1991 the first metal-bodied Atlantic for Jack was finished. Many of you have seen it as it has been in America several times.

Since finishing the Braam-Ruben car, Koux has built five more with aluminum bodies, which are widely dispersed: The Braam-Ruben car is in Dubai, the green one that was in the Brooks May 2000 sale is in Germany, one is in Japan, his most recent is in Austria, and two more are in France (one of them used quite frequently).

Since finishing the Braam-Ruben car, Koux has built five more with aluminum bodies, which are widely dispersed: The Braam-Ruben car is in Dubai, the green one that was in the Brooks May 2000 sale is in Germany, one is in Japan, his most recent is in Austria, and two more are in France (one of them used quite frequently).

A second one in Germany has an interesting story to go with it: Erik built it for Erich Traber from Switzerland. Traber later sold it to a German collector who decided to sell it after several years. A car dealer friend of this collector suggested that he advertise it as "one of only five built." Anyone familiar with Bugattis would surely be suspicious since the price was too low for an original and too high for a copy. Nonetheless, the car was promptly bought, no questions asked, by the VW group. It didn't stay long in their Berlin showroom once they realized it was a Koux and not an original, but they have proudly kept it in Wolfsburg with their Royale T41-41111 and show it frequently. It was featured in Classic Cars, March 2004, and again in Octane, September 2006.

Of the earlier, fiberglass-bodied examples, there are a few updates: The Alfa 2600 engine in the first has been replaced with a Bugatti T57 engine converted to T57SC specifications, two are in Denmark still with Jaguar engines, one of the two sent to John North was unfinished when sold to British dealer C. Howard. Howard had Crailville, a coachbuilder in England, use the Koux fiberglass shell to make an aluminum body, and the completed car has belonged to Jay Leno for years. The fiberglass body of another has also been replaced with aluminum. So there are only five left, two of which have Jaguar engines.

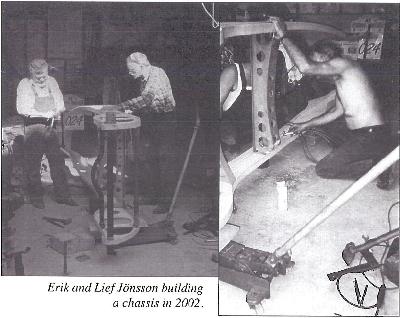

Erik's working setup revolves around a "small (1,300 square feet), messy" workshop in the old horse barn of the vineyard house where he now lives near Apt in the south of France. This is very similar to the workspace he had when he lived on a country estate about 15 miles north of Copenhagen. He relies on highly professional suppliers for chassis frames as well as other large parts when Bugatti originals are unavailable. With his lathe, drilling machines, milling machine and welding equipment, he makes most of the smaller parts himself, duplicating the many originals that have passed through his hands over the years and can still be found occasionally and used. In answer to my question, "What is the hardest part of building an Atlantic reproduction?" Erik replied, "Probably to make the panel beater understand that I want an exact copy of the fiberglass master and not his own interpretation." The panel beater follows this instruction to the letter. Erik does the interiors himself-upholstery, carpets and headlining. The dashboards and window frames are made by his patternmaker. All the assembly is done by Erik in the workshop, working mostly alone. He gives each car a chassis number but no visible badge or emblem.

Erik's working setup revolves around a "small (1,300 square feet), messy" workshop in the old horse barn of the vineyard house where he now lives near Apt in the south of France. This is very similar to the workspace he had when he lived on a country estate about 15 miles north of Copenhagen. He relies on highly professional suppliers for chassis frames as well as other large parts when Bugatti originals are unavailable. With his lathe, drilling machines, milling machine and welding equipment, he makes most of the smaller parts himself, duplicating the many originals that have passed through his hands over the years and can still be found occasionally and used. In answer to my question, "What is the hardest part of building an Atlantic reproduction?" Erik replied, "Probably to make the panel beater understand that I want an exact copy of the fiberglass master and not his own interpretation." The panel beater follows this instruction to the letter. Erik does the interiors himself-upholstery, carpets and headlining. The dashboards and window frames are made by his patternmaker. All the assembly is done by Erik in the workshop, working mostly alone. He gives each car a chassis number but no visible badge or emblem.

Erik's Atlantics are driven too. Before selling them, he has taken them to such diverse events as the Tour of Sicily fifteen years ago, a Tuscan rally five years ago, and several Enthousiastes Bugatti events in Alsace.

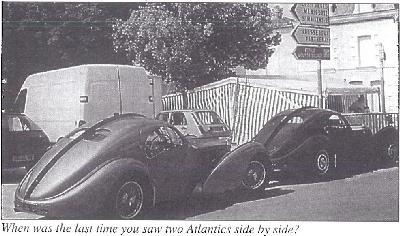

Charles Robert, owner of the metallic gray Koux Atlantic, has driven it to many events in France, including one at which it was photographed nose-to-tail with the dark-green one that Erik was still using himself (Pur Sang, vol. 39, no. 3) . Erik also drove Jack Bream-Ruben's car in a rally at Pebble Beach in 2003 after

which he and Jack visited the Concours d'Elegance there. When the Concours ended, the men who were supposed to take the car to its next stop attached their ropes to the front axle of EXK6. As they began to take it away, three men jumped them, and they had to do some serious persuading to convince them that Jack's car was up the hill at the time, gracing the Blackhawk exhibit.

which he and Jack visited the Concours d'Elegance there. When the Concours ended, the men who were supposed to take the car to its next stop attached their ropes to the front axle of EXK6. As they began to take it away, three men jumped them, and they had to do some serious persuading to convince them that Jack's car was up the hill at the time, gracing the Blackhawk exhibit.

Bream-Ruben enabled some other comments about the car, which he sold very reluctantly after over eighteen years. He sold it only because the bumpy roads in The Netherlands repeatedly damaged the exhaust, requiring several very costly replacements. Besides the "wonderful sound" of the supercharged engine, "it drove like a modern car, steering light, brakes strong and lots of power. I must have driven it more than 40.000 km, more than any other Atlantic owner. Wherever it went it attracted large groups of people. Sometimes I was asked if I were Mr. Lauren, and of course I said I was. Mind you, I dearly miss the car, and I feel bad about selling it. The poor car is probably now in a nice warm room in Dubai , never to be driven again. A great shame. It really deserved better."

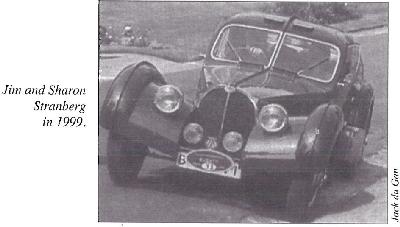

Jim Stranberg, restoration expert and ABC member. emailed me to say, "driving Erik's Atlantic in '99 was a wonderful experience. The car ran flawlessly, except for a little overheating, during the two weeks Sharon and  I had the car. The car handled very well both in the city and in the country, and it is very comfortable to ride in. Erik's Atlantic compares very well with Dr. Williamson's. which I codrove on the Colorado Grand."

I had the car. The car handled very well both in the city and in the country, and it is very comfortable to ride in. Erik's Atlantic compares very well with Dr. Williamson's. which I codrove on the Colorado Grand."

There are several sites on the internet which show pictures of Koux Atlantics along with ABC member Jay Leno's Crailville-after-Koux example.

The car that Erik's bodybuilder had planned to build for himself using the borrowed fiberglass mold during the early stages of work on the Bream-Ruben car remained unfinished over the years. Erik has recently taken over the project himself and plans to finish it "as close as possible to EXK6 the day it left the factory." He says it will be his last Atlantic, and he is going to keep it. It will share garage space with his superb recreation of T575-57385, the "lost" Jean Bugatti roadster.

The author thanks Erik Koux for his generous help with this article.

First published in ABC-magazine Pur Sang

Top picture: Jack Braam-Ruben's car, photo Jaap Horst